Enter by the narrow gate; for wide is the gate and broad is the way that leads to destruction, and there are many who go in by it. Because narrow is the gate and difficult is the way which leads to life, and there are few who find it. [Matthew 7:13-14]

In the Sermon on the Mount, in our Lord Jesus Christ’s instructions to his followers (and therefore, us), he tells us to choose the narrow path, the one which most requires self-discipline. To the first Christians, this narrow path stood out clearly – it was the one opposite that of the world, the one that frequently led to martyrdom. By the 4th century, when the Church had become not only tolerated but favored by political authorities, the narrow path was more difficult to discern. St. Anthony the Great established a new way to follow the narrow path – that of monasticism. Many followed his example in retiring from the world to a desert place to practice the solitary ascetic life of prayer and fasting more intensely. The “desert” became the wilderness as monasticism spread out from the Middle East to other parts of the world. Through the examples of St. Jerome, St. John Cassian and St. Benedict, this way of life became known throughout the West. Just as monks were practicing the ascetic life in Egypt, Palestine, Syria, and Italy, a young prince in a remote part of the world was also being drawn toward this narrow path.

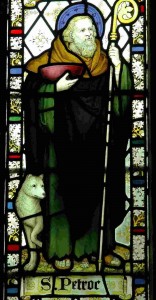

Petroc was the son of King Glywys, who desired that his son share in ruling a portion of his Welsh kingdom. But Petroc longed to pursue the ascetic life, so he traveled to Ireland to learn from the monks there, where Christianity had been thriving since the end of the second century. After this period of study, Petroc settled in Cornwall at an already-established monastery, where the lives of the monks were balanced between prayer and work.

Here the monastic “desert” consisted of small islands and remote lands isolated by watery inlets. Like other ascetics surrounded by water, the monk Petroc spent many hours standing in the water near the monastery, reciting the Psalter and saying his prayers. Also like many other saintly monks, Petroc is said to have had a great love and affinity for animals. The story is told of how a local Cornish king was converted to Christianity through the action of the saint: The king and his companions, hunting near the place where Petroc was praying, were chasing a stag which took refuge in the monk’s cell. He intercepted the hunters in order to save the animal, and the king was so impressed by this strange behavior that he received instruction from Petroc and was baptized into the Church taking the new name Consantine.

St. Petroc founded many churches in Cornwall and, in the tradition of his Irish teachers, made a seven-year pilgrimage to Rome and Jerusalem. He made missionary journeys, possibly as far away as India. When he returned to Cornwall, Petroc sought the greater solitude of hermit life and set up a cell more deeply in the wilderness, at Bodmin. As so often happened with those who followed this narrow path of monasticism, the world which they had left behind followed them – men seeking conversion and counsel and those who wished to become disciples. Another monastery grew up here, with St. Petroc as its abbot. Having faithfully followed the narrow path for most of his life, St. Petroc fell asleep in the Lord on June 4 about the year 564.

Not all of us can – or should – become monastics. God chooses only some people for that particular vocation. But each of us is required to determine how to enter by the narrow gate, to follow the narrow path in our lives. May the prayers of St. Petroc and those of all the saints be with us as we struggle to discern the way.