Feast Day ~ July 8

Feast Day ~ July 8

We have heard this story before: a well-educated young man of noble birth decides to reject the family wealth and political aspirations and become a monk. Then, after years of prayer, fasting, meditation, and study of Holy Scripture he feels moved to leave the familiarity of his native land and travel far to tell others about Christ.

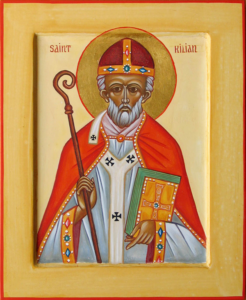

Like many before and after him, St. Killian fits this description. His life began in Ireland (in County Cavan) around the year 640. His schooling was primarily in the School of Ross, a monastic institution noted for the thorough education of its students who came from all over Europe. According to some reports, Kilian entered another famous institution, the Monastery of Hy, which later came to be called Iona. It was here that Kilian pursued the ascetic life of a monk.

How long must the monk Kilian have felt the pull of the peregrinatio, the religious pilgrim who would enter voluntary exile from his homeland? In 686, he and eleven companions responded to this pull and left Ireland for the land of the Franks. Richard Fletcher, in The Barbarian Conversion, states that:

The ideal of pilgrimage was absolutely central to the missionary impulse of the early medieval period. It may also be said of the pilgrimage of exile that it was a form of martyrdom. The pilgrim severed the ties that bound him to worldly society, so that pilgrimage was a kind of social death.

In some accounts, Kilian was consecrated as a bishop before leaving Ireland and there were other ordained monks among his fellow travelers. Sailing on the Rhine and the Main Rivers, The group arrived in Wurzburg, where the Thuringian (or Frankish) Duke Gozbert was the ruler. Nine of this group of monks departed for other missionary endeavors, leaving Kilian, the priest Colman and the deacon Totnan in Wurzburg. In only a few years, through example and persuasion, these pilgrim/missionaries had convinced the duke of the truth of Christianity and baptized him and many of his subjects.

Desiring a stronger formal authority for their mission, the three traveled to Rome, where they received the blessing of Pope Conon for this work. When they returned to Wurzburg, the missionaries discovered that Duke Gozbert had married his brother’s widow, Geilana, a woman who had resisted conversion to Christianity.

Here was a problem which missionaries in every age have faced. How much can the Church accommodate the practices of the world, especially regarding the Sacrament of marriage? Pagan cultures had developed their own rules for who could be married to whom, and these often involved the merging of political and financial interests. But the Church also had rules which restricted marriage between persons who were already related to each other by blood (evidently, the relationship of Gozbert and Geilana was more than just that of brother- and sister-in-law).

Pope St. Gregory the Great had responded to St. Augustine of Canterbury’s concerns on this issue as he encountered pagan marriage customs among the peoples of Britain; it would be an issue in the next century for St. Boniface in his mission to Germany, in the 10th century with Khan Boris and the Bulgarian people as they considered conversion to Christianity, and even today when people who practice polygamy are brought into the Church.

Bishop Kilian took a hard line with Duke Gozbert. He tried to dissolve the marriage, declaring it against Christian precept, and so he now faced a different kind of martyrdom. When Gozbert was away from the castle, Geilana arranged to have the bishop, Fr. Colman and Deacon Totnan beheaded as they were preaching in the town square.

St. Kilian’s work did not die with him, however. St. Boniface, in his missionary activity in the next centuryy, continued to “tend the field” which had been “planted” by St. Kilian. St. Burchard was appointed by St. Boniface as the bishop of Wurzburg and after building a cathedral on the site of the martyrdom, Bishop Burchard had the relics of St. Kilian translated to the cathedral where they remain for veneration today. Kilian was declared a saint and his name was included in early martyrologies in Germany and Ireland.

Would we, like St. Kilian, be willing to leave home and family to be missionaries in a foreign land? (Would we be willing even to tell our neighbors and co-workers about the love of Christ?) Would we, like St. Kilian, be willing to confront someone in a position of power and authority with the truth of Christian principles? Would we, like St. Kilian, be willing to accept death (even the death of our social positions or businesses) as the consequence of this confrontation?

May St. Kilian, Apostle to Franconia, intercede for us that we may have the strength to follow his example. Holy Kilian, pray for us.

Resources: David Farmer, Oxford Dictionary of Saints; Peg Coghlan, Irish Saints; Peter Brown, The Rise of Western Christendom; Richard Fletcher, The Barbarian Conversion; article from Wikipedia.