(Feast Day – August 25)

We have heard much lately about synod meetings and councils of the Church – those of the Holy Synod of Antioch meeting in Damascus, meetings of our local synod of North American bishops, meetings of SCOBA (the Synod of Canonical Orthodox Bishops in America), and the bishops of the “mother” countries meeting in Chambasy, Switzerland to discuss the Orthodox “diaspora.” This is how the Church has always made decisions. Since the first Council of Jerusalem about the year 49, when the Apostles agreed (with the aid of the Holy Spirit) that Gentile converts to the new religion did not have to become Jews first and be circumcised and follow the Mosaic dietary laws, the conciliar approach has been maintained in the Orthodox Church.

The decisions of the most important councils – the seven Ecumenical (or world-wide) Councils – are well documented and celebrated by the Church for their defining decisions. Some other synods or councils – such as the Council of Florence in 1438-9 – are infamous for decisions made in desperation which were later reversed.

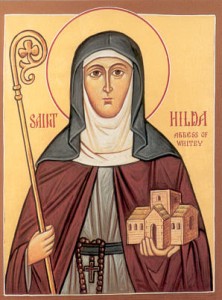

But there have been numerous smaller synods and councils through the centuries which have affected the course of Christianity in parts of the world. Decisions have been made at these meetings which have brought about unity or have separated Christians from their brethren in other places. St. Hilda, 7th century abbess of the Monastery of Whitby in England, served as the host for a synod which brought the Church in that remote part of the world into greater unity with Christians throughout the world.

Hilda (Hild) was born in 614 into the royal households of Northumbria and East Anglia, but her father was in exile at the time of her birth and died several years later. Hilda was subsequently raised at the court of her uncle Edwin, who re-conquered his territory in Northumbria to reign as king.

In this setting, Hilda’s life was greatly affected by the fruits of the missionary venture to England begun by St. Gregory the Great around 597. After King Edwin’s first wife died in 625 (when Hilda was 11 years old), he took another wife, Aethelburga, the daughter of the King of Kent, who was a Christian. Aethelburga brought her chaplain, Paulinus, to court with her. A Roman monk, he had been sent by Pope Gregory to assist with the work of St. Augustine and the other monks who were evangelizing the kingdom of Kent.

Two years later, Edwin gave up his pagan practices to become a Christian. Much of his household, including 13-year-old Hilda, was baptized with him in the river at York on April 12, 627. The dramatic story of Edwin’s long and thoughtful journey toward Christianity, the “deal” he made with God, and his eventual baptism were preserved by St. Bede in his History of the English Church and People.

Five years later, King Edwin was killed in battle and all in his household fled the kingdom for safety in Kent. No details are known of Hilda’s life during this time. There is no record of a marriage, although as a royal princess she still offered political advantage for an arranged marriage. It is not until she was 33 years old that we hear of her activities again. At that time, she was planning to join her sister in a monastery in Chelles, France (near Paris). But her plans were changed at the last minute when she received an urgent request from Bishop Aidan of Lindisfarne. She was asked to return to Northumbria to help found a monastery at the mouth of the river Wear.

As a monk, Aidan had been part of the Celtic Christian tradition which had been flourishing since before St. Gregory’s Roman monks arrived in Kent. With monastic centers in Iona (Scotland) and Lindisfarne, the monks had maintained the Christian faith and some practices which were different from those of the Romans. The most problematic difference was the way of calculating the date of Easter.

Hilda accepted the challenge offered by Bishop Aidan, began the monastery and served as its abbess, using a rule based on that of St. Columbanus, another Celtic monastic leader. Hilda went on to serve as abbess in another monastery at Hartlepool and in 657, founded an abbey at Streanaeshalch (a name later changed to Whitby). This abbey was a double monastery, with separate cells for men and women who shared a chapel and a ruler – in this case, Abbess Hilda.

Under Hilda’s leadership, the monastery very quickly became a great center for learning and the abbess’ counsel and advice were sought by secular rulers as well as priests and bishops. Five bishops received their monastic training in this monastery. Abbess Hilda also encouraged the talent of a simple cowherd, Caedmon, who composed epic Anglo-Saxon poetry which incorporated Christian themes.

Since the death of Hilda’s uncle King Edwin, there had been a succession of rulers in Northumbria and those who were Christian had been taught the Celtic traditions. When marriages (including that of the current King Oswiu) with those who had been brought up in Roman ways occurred, the result was very confusing and detrimental to the health of the Church in this part of the world. In the words of St. Bede: “It is said that the confusion in those days was such that Easter was sometimes kept twice in one year, so that when the King had ended Lent and was keeping Easter, the Queen and her attendants were still fasting and keeping Palm Sunday…this dispute rightly began to trouble the minds and consciences of many people, who feared that they might have received the name of Christian in vain.”

So in 664, the king called a Church Council to determine which of the two traditions his kingdom would adhere to. Abbess Hilda was asked to host this Council in the abbey at Whitby. The main parties in the discussions at the Council were Bishops Colman and Cedd, representing the Celtic viewpoint, and Bishop Agilbert and priests Agatho and Wilfrid, who were there to speak for the Roman traditions.

St. Bede records in detail the proceedings of the Council. Bishop Colman explained that the Celtic practices had been passed down from generation to generation of monks, priests and bishops and that they had originated with the Apostle and Evangelist, St. John, who had been our Lord’s “beloved” disciple. When Bishop Agilbert was to speak, he requested that Wilfrid speak in his place because he could speak directly in the English language and not have to go through an interpreter. Wilfrid then proceeded to explain (in not very diplomatic terms – calling Bishop Colman “stupid”!) that St. John’s observance of Easter was at a time in the early Church when the laws of Moses were still being observed in order to avoid offence to the Jewish Christians. He told how the Church had moved away from tying Pascha to Passover and how the Ecumenical Council of Nicaea in 325 had confirmed the dating of the “feast of feasts” in a manner which had long been practically universal. Wilfrid reported on the celebration of Easter in Italy and Gaul, Africa, Asia, Egypt, Greece – places he had either traveled to or communicated with.

Wilfrid’s arguments were persuasive and, after much debate about this and other issues (such as the style of the monastic tonsure) those present at the Council, under the king’s leadership, agreed to adopt the Roman practices. Colman resigned his bishopric and returned home with the others who could not make the change. Abbess Hilda’s intentions had been to vote for the Celtic traditions but she was won over by Wilfrid’s arguments and brought her abbey into conformity with the rest of Christendom. Through prayer, discussion, argument, reasoning – and with the aid of the Holy Spirit – a decision for the good of the Church in a particular land had been accomplished through the convening of a Council.

Hilda continued her good work in the monastery at Whitby, providing loving care and counsel to nuns and monks, building up the library and encouraging study, and inspiring others to holiness of living. According to St. Bede, “Christ’s servant Abbess Hilda, whom all her acquaintances called Mother because of her wonderful devotion and grace, was not only an example of holy life to members of her own community; for she also brought about the amendment and salvation of many living at a distance, who heard the inspiring story of her industry and goodness.”

After a painful illness of six years, St. Hilda fell asleep in the Lord. Her death was marked by the miraculous vision of her soul being carried to heaven by angels, a vision seen by one of the Whitby nuns and another nun in a monastery which St. Hilda had founded earlier in life.

May the Church in our time continue to seek the aid of the Holy Spirit when councils are held for making decisions about Church governance and practice. And may St. Hilda intercede for our bishops and other leaders who maintain this apostolic conciliar approach. Holy Hilda, pray for us.