As our nation was being formed from the settlements in the 13 colonies on the East coast, a chain of events was beginning on the other side of the world that would eventually be of great spiritual significance for this new country. A young adolescent man, the son of a merchant (born around 1758) entered a monastery near St. Petersburg, Russia, and took the name Herman. In 1779, as the Revolutionary War for American Independence was being waged, the young monk transferred to the famous Valaam Monastery, which had been founded in the 12th century by Ss. Sergius and Herman on an island in Lake Ladoga in Russian Finland. Although Herman was well thought of by his fellow monks, he preferred the life of a hermit, spending all his time except Sundays and major feast days in a dense forest on the island.

With Russian expansion of trade in the New World on the West Coast, the Orthodox Church was moved to send missionaries to minister not only to the men involved in trading but also to evangelize the native Aleuts. So, in 1793 – when George Washington was still president of the new nation on the East Coast – ten monks, Herman among them, began the arduous one-year journey from Valaam across Russia and Siberia to Alaska, the longest missionary journey ever made. They landed on Kodiak Island on September 24, 1794.

The missionaries began their work by learning the Aleutian language so that they could teach the people about our Lord Jesus Christ. They soon discovered that their responsibilities to the native people would include more than teaching and preaching. The Russian-American Company was headed by Alexander Baronov, a tyrant who treated the natives as slave laborers. Baronov, whose life was far from that of a good Orthodox Christian, was opposed to the presence of the monks and he did everything in his power to keep them from successfully carrying out their work.

With the strengthening consolation of prayer and fasting, the monks carried on, despite the difficult circumstances. Longing for the solitude of his Valaam hermitage, Herman moved to Spruce Island, about a mile away from Kodiak, calling it “New Valaam.” He made a hut for himself and planted a garden of turnips, potatoes, cabbage, garlic and horseradish (elements of a good Russian diet!).

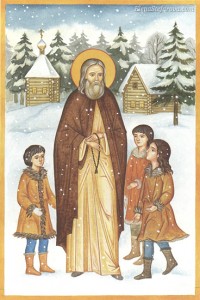

Herman continued his work with the Aleuts, especially the children whom he loved dearly. When a ship from the U.S. brought a fatal disease to Alaska and many natives became sick and died, Herman nursed the ill, ministered to their families, buried the dead, and cared for the orphans. He built a school, a children’s home and a chapel on spruce Island and brought the orphans there to live permanently at the end of this epidemic.

Herman had been given the gift of prophecy and miracles. He himself had experienced a miracle of healing early in his monastic life: he had been very ill with an abscessed sore on his face. After many days of pain and fever, he prayed fervently to the Theotokos for aid, wiped his icon of her with a cloth, and then placed the cloth on his face. When he awoke from sleep, he was completely healed. Miracles such as this continued throughout his life. His gift of prophecy was most often used to comfort the fears of the Aleuts and his fellow monks or to stir repentance in the heart of one of the wayward Russian workmen.

Many native people came to accept Christianity and be baptized. The monks performed marriages and ended polygamy among the people. There was some native resistance, the strongest resulting in the murder of Hieromonk (later St.) Juvenaly. Despite this, the Holy Synod in Russia was impressed with the possibilities for evangelization in this new world. Archimandrite Ioasaph was called to return to Russia for consecration as a bishop for Russian America, with the hope that he would eventually train and ordain native priests. However, the ship which was bringing the new bishop and his assistants back to Alaska sank and all aboard were drowned. This severe setback, coupled with the emboldened Baranov’s persecutions, caused three of the remaining four monks to request transfer. Only Herman remained, faithfully continuing his pastoral work on Spruce Island.

There were two happy events which occurred to aid Fr. Herman in his work. In 1817 (shortly after the signing of the treaty ending America’s War of 1812), the cruel Baranov was replaced by Simeon Yanovsky as manager of the Russian-American Co. Yanovsky had heard horrible tales about this “wild” monk, but when he met Herman, an immediate bond of friendship was established. Later in life, Yanovsky would himself become a monk, and he provided the world with most of the facts known about Herman’s life. The other helpful event was the vocation of a young woman, Sophia Vlasova, who asked to live as a monastic on Spruce Island and assist Fr. Herman in working with the children.

In 1837, with Andrew Jackson as president and westward expansion proceeding rapidly, Fr. Herman’s earthly life ended. He was nearly 80 years of age and weary from a long life of faithful service in this difficult mission field. He had foretold his death, asking his followers to light candles and read from the Book of Acts. He instructed them to cover his face and bury him immediately after death. Disobeying these instructions, his spiritual children kept his body (which exuded a beautiful floral fragrance) lying in state from his death on December 13 for several weeks before burial. Herman was immediately revered as a saint. 132 years later, the Russian Orthodox Church in America (now OCA) made an official declaration of sainthood and completed the canonization on August 9, 1970.

St. Herman of Alaska, Elder and Wonderworker, was the first to be declared a saint of the Orthodox Church on this continent. As Alaska was later sold by Russia to the United States and eventually became a state, St. Herman is a saint of our own country. May he intercede in heaven for this nation, for its leaders and its people.