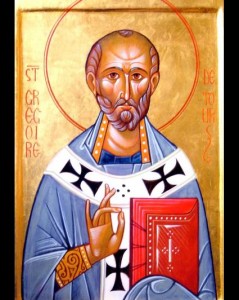

Every Christian knows how arduous the quest for holiness is, how difficult the struggle to overcome the passions and to live a Christ-like life. Converts to Christianity are also aware of the time that it takes to acquire the Christian “mind-set” – to take on the attitudes of one who has died to sin and risen with Christ in baptism and chrismation. How much more difficult it must be for an entire people who convert to Christianity to change their ways of thinking and acting. We know about these difficulties with one group of people through the writings of St. Gregory, bishop of Tours in the late 6th century.

Gregory, named Georgius Florentius Gregorius at his birth in 538, was from an old Roman family of devout Christians. Among his ancestors and relatives were numbered a martyr of Lyons, monastics, and numerous bishops, as well as senators. In fact, Gregory counted among his ancestors thirteen of the eighteen men who preceded him as bishop of Tours.

As a child, Gregory had an innocent and trusting faith in God and his saints. Later in life he wrote of two visions he received in dreams, not understood at the time, that led to miraculous healings. In both visions, a man (an angel?) appeared to him and told him how his father could be cured of the illness he was suffering from, making reference to the book of Joshua and that of Tobit. After reporting these dreams to his mother, who wisely recognized them as heavenly visions and made use of the remedies, Gregory’s father’s health was restored.

Rather than sending their spiritually precocious child to a monastery after these visions, Gregory’s parents decided that he should have a thorough education first, and they entrusted him to his uncle (St.) Gallus, bishop of Clermont-Ferrand. Gregory also frequently visited other related ecclesiastics, (St.) Nicetius, his grand-uncle who was bishop of Lyons, and his cousin (St.) Eufronius, who was bishop of Tours. With this overwhelming influence of saintly men of the Church, it was natural that Gregory should adopt the clerical life also. He was ordained deacon in 563, and when his cousin Eufronius died in 573, the people asked for Gregory as their next bishop.

Tours was an important pilgrimage site for Christians. It was there that St. Martin – revered around the world – had been bishop and where his relics still effected miracles. The city’s bishop was a Metropolitan, responsible not only for his own diocese but also for four others. The poet Venantius Fortunatus celebrated Gregory’s consecration with the following words, part of a long poem for the occasion:

Applaud, O fortunate people, whose desire hath now been accomplished. Your hierarch arriveth; it is the hope of the flock that cometh. May lively childhood, may the old and bent with age celebrate this event; may each proclaim it, for it is the good fortune of all.

Tours was in the Roman territory of Gaul, which had been conquered by the pagan Franks when, under the leadership of their king, Clovis, they defeated the Roman army at the Battle of Soissons in 486. Clovis was married to an Orthodox Catholic Christian, Queen Chlotild, and he eventually converted to the faith (while many of the other pagan tribes who invaded Europe became Arians). As the Franks populated the area and mingled with the remaining Romans, they gradually accepted Christianity over their former pagan beliefs. But conversion of behavior was slow in coming, as Bishop Gregory attests in his History of the Franks, which describes history as filtered through the wars and disputes of the royal families of the Merovingian dynasty. The book contains story after story of murder, treachery, deceit and royal rivalries.

Bishop Gregory had a remedy for this behavior, one that would bring the people closer to obedience to God’s commandments and true faith in him. While The History of the Franks may have been written to expose the people to the worst of their faults, Gregory also wrote eight Books of Miracles, which praise the virtues of the saints to be emulated by those who follow. Gregory stated his purpose in his preface to one of the books, The Glory of the Blessed Martyrs: “We ought to pursue, to write, to speak that which edifies the Church of God and by sacred teaching enriches the needy minds by the knowledge of perfect faith.” Bishop Gregory himself had experienced miracles of healing and guidance through the influence of the saints, and he wanted his people to know that the saints of God are always near and ready to intercede for sinners.

Another desire of the bishop was to provide his flock with churches whose beauty would lead them to greater devotion. He first restored and beautified the shrine church of St. Martin, which had been heavily damaged by fire. In his description of the basilica in his native Clermont, we have a picture of what the churches in Gregory’s day were like:

It is 150 feet long, 60 feet wide inside the nave, and 50 feet high as far as the vaulting. It has a rounded apse at the end, and two wings of elegant design on either side. The whole building is constructed in the shape of a cross. It has 42 windows, 70 columns, and eight doorways. In it one is conscious of the fear of God and of a great brightness, and those at prayer are often aware of a most sweet and aromatic odor which is being wafted towards them. Round the sanctuary it has walls which are decorated with mosaic work made of many varieties of marble.

These wonderful churches were often also used as places of sanctuary, and St. Gregory sometimes had to endure the presence of very unsavory characters who sought refuge in the church to escape their enemies, always praying for their repentance and change of behavior. The bishop also had many visitors who brought the wider world to his doorstep. He knew about the sites of the Holy Land from an eye-witness and, from an exiled Armenian bishop, he learned about the Church of the Forty-eight Martyrs and of the fall of Antioch. St. Gregory was called upon to act as arbiter in civil disputes and sometimes had to argue with kings and search out the truth when opposing sides gave different stories. The role of a bishop in 6th century Gaul was indeed varied.

After twenty-one years of faithful service to God as a bishop for his people, St. Gregory died in 594. Three hundred years later, the story of his life was written by Odo (879-942), a monk of St. Martin’s monastery in Tours, who later became abbot of the famous monastery of Cluny. Abbot Odo wrote of St. Gregory’s death and burial, “One is not entirely sealed in the tomb if his word itself is living in the world.”

May we take to heart those things which St. Gregory knew to be of great importance – veneration of the saints and the need for beauty in our worship – and may St. Gregory intercede for us as we strive for perfection.