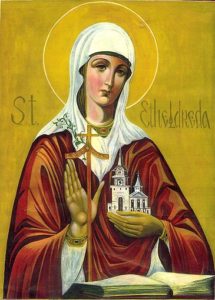

One of the most popular saints of 7th century Anglo-Saxon England was St. Etheldreda, who spent her entire life going against the ways of the world.

Given the name Æthelthryth (popularly called Ethedreda and sometimes Audrey) by her parents (Anna, the king of East Anglia, and his wife Hereswyda), the girl was taught Christian precepts in childhood. She and her elder sister, Sexburga, and her younger sister, Withburga – both of whom also became saints of the Church – were faithful in attendance at the services of the Church, in their private prayers and in studying God’s word.

Etheldreda grew to desire nothing more than to remain a virgin and devote her life to a more intense version of her childhood religious practices. But she was a princess and even in this far-flung corner of the civilized world, the kingdom expected its princesses to dress finely, to entertain lavishly, and to contract politically advantageous marriages.

Etheldreda’s early love of lace collars and necklaces would later become a source of regret and repentance. Conquering that influence of the world around her, the girl continued to insist on her desire to be a monastic. But after her sister, Sexburga, had been given in marriage to the King of Kent, a marriage which brought with it important political ties was made for Etheldreda to Tondberht, a prince of another tribe in the area. As a marriage gift from the groom, Etheldreda was given the Isle of Ely. Still insisting on her desire to lead a celibate life, Etheldreda was able to convince her new husband that they should continue to live as virgins. After only three years of marriage, Tondberht died and his widow retired to Ely to finally pursue a quiet life of prayer away from the demands of court life.

But the young princess was still an important prize in the everchanging political world around her. Her relatives insisted on another expedient marriage, this time to Ecgfrith, the heir to the throne of Northumbria, who was at the time a young teenager.

Once again, Etheldreda told her betrothed about the vow she had made to remain a virgin and he agreed to honor that vow. While this may seem highly unusual to us in the 21st century, many of the Fathers of the Church have written about the value of such a life if it is agreed to by both husband and wife. Etheldreda had as her spiritual advisor Bishop (St.) Wilfrid and he gave his blessing for the couple’s decision.

As Ecgfrith reached manhood, however, and succeeded his father as King, he changed his mind about the kind of life his wife wanted to live. He realized that he needed to produce an heir and have a family around him to support him in his rule of the kingdom. His efforts to bribe Bishop Wilfrid to counsel Etheldreda to break her vow were unsuccessful. When he attempted to force his wife to meet his demands, she fled to Ely and Bishop Wilfrid tonsured her as a nun. He released Ecgfrith from the marital vows and he later remarried.

Finally free to devote her life entirely to prayer and contemplation, Etheldreda first served as a novice at a monastery in Coldingham where her aunt Ebbe was the abbess. In 673, she founded a double monastery at Ely and served as its first Abbess. She restored an old church which had been destroyed by the pagan king of Mercia. Here the nun could spend her days as she had always desired – in silence, in prayer, in austerities which included wearing only rough woolen clothes and eating only one meal a day. This was the path by which she sought sanctification.

After seven years, Abbess Etheldreda developed a tumor on her neck (which she interpreted as a sign that she had not fully repented of her earlier sin of vanity in wearing fine jewelry) and she passed to the next life on June 23 in the year 679. She was buried, as she had requested, in a wooden box.

Etheldreda’s sister, Sexburga, had meanwhile been widowed after years of marriage to her royal husband and raising four children. While she was queen, she had founded a monastery to which she retired upon her husband’s death. When her sister died, Sexburga then moved to Ely and succeeded her as abbess there. Seventeen years after Etheldreda’s death, Sexburga had her tomb opened in order to translate her relics to a stone sarcophagus in a place of greater honor. Bishop Wilfrid and the physician who had attended Etheldreda in her last illness were present, and all were amazed to find not only that her body was incorrupt and all the clothing intact, but that the tumor was completely healed and her neck returned to its normal size.

St. Etheldreda’s shrine became a place of pilgrimage for many. Although her monastery was destroyed during the Danish invasions, it was rebuilt in 970 as a monastery for monks only and the shrine remained a place for veneration. The saint’s shrine was stripped in the twelfth century to pay a fine which the then bishop had incurred and there were several more translations of the relics before Ely Cathedral, built over the original site, was consecrated in 1252. It was not until the destruction at the time of the Protestant Reformation that the centuries of veneration came to an end. However, through the mercy of God, some of the relics had been taken to a London chapel used by the bishops of Ely which was then turned over to the Spanish ambassadors to England, allowing these relics to escape destruction. Through the centuries, miracles were reported in association with veneration of the saint’s relics.

St. Etheldreda’s life of holiness was accomplished through her determination to go against the ways of the world around her, to remain a virgin and dedicate her body, as well as her soul, to Christ. May she intercede for monastics and others who lead a celibate life and for all of us as we struggle to overcome the temptations and distractions of the world.