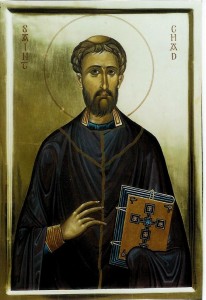

During the presidential election of 2004 we heard much about “chads”. After the reporters had exhausted their supply of words about such things as “dimpled chads” and “hanging chads”, they moved on to enlighten us about the country Chad and then to teach Americans – many for the first time – about St. Chad, who was bishop of Mercia in 7th century Britain.

The story of St. Chad’s life (which is similar to that of other holy men Christians revere as saints) seemed to resonate with many people as having something profound to say about disputed elections.

Born around the year 620, Chad was one of four brothers, all of whom became priests and two (Chad and Cedd) who were consecrated as bishops. Chad became a monk, with St. Aidan of Lindisfarne as his spiritual father. He eventually succeeded his brother, Cedd, as abbot of Lastingham Abbey in Yorkshire.

The Council of Whitby, in 664, proclaimed the Roman manner of calculating the date of Pascha (as opposed to the system used by the Irish) to be the Orthodox Catholic use. Soon after this conciliar decision, King Oswy called for the priest Wilfrid, who had spoken eloquently at Whitby, to be consecrated Bishop of York.

Wilfrid traveled to Gaul and with great pomp and ceremonial was made a bishop. However, his prolonged stay in Gaul left the people of Northumbria without a bishop and so, during his absence, Chad was chosen to lead the Church. En route to Canterbury to be consecrated by Archbishop Desduit, Chad learned of the Archbishop’s death, so he received his consecration from a “questionable” source – British bishops still following the Celtic customs now considered “non-canonical”.

However, the holy manner of this humble man and his dedication to the care of his flock soon made him beloved by the people. In the words of St. Bede, “Chad immediately devoted himself to maintaining the truth and purity of the Church, and set himself to practice humility and continence and to study.”

When Wilfrid finally returned from Gaul, he found Chad in his place as Bishop of York, so he acquiesced to Chad and retired to a monastery at Ripon. But by now (669), a new Archbishop of Canterbury had been appointed – Theodore of Tarsus, sent by the pope in Rome after the British candidate died traveling to Rome for consecration.

The controversial bishopric was brought to the attention of the new archbishop. Theodore first decided to reinstate Wilfrid as the rightful and properly consecrated Bishop of York. So now, Chad graciously gave way and retired to a monastery, exclaiming that he had never felt worthy of the position. But, as described by Peter Brown in The Rise of Western Christendom, “Within a few years, this man [Theodore], a native of what is now southeastern Turkey, who remembered the city of Edessa and the great churches and monuments of Constantinople, found himself at Lindisfarne, blessing a church made of carved oak, thatched with reeds…Used to the small cities of Asia Minor and Italy, where the bishop was expected to act as a ‘father’ to the faithful in a small region, the vast ecclesiastical ‘empire’ of Wilfrid shocked him.” Because of the great distances and also due to newly successful missionary efforts in the Kingdom of Mercia, Theodore made the decision to redefine the diocesan boundaries. Taking part of the area which had been in Wilfrid’s diocese, he created a new diocese of Mercia, with Litchfield as the see city, and appointed (and re-consecrated) Chad as its bishop.

This humble bishop now returned to the tasks of tending to a larger flock beyond the monastery walls. As he had previously done, he walked from village to village, wherever he went (“after the example of the Apostles”, according to Bede), refusing to ride about on a horse like a nobleman. But the Archbishop, who was concerned for the health of his clergyman, lifted him up to a horse and ordered him to ride about his diocese. Chad humbly obeyed his superior.

The work in the new diocese was difficult, but Bishop Chad’s efforts bore much fruit. Perhaps the most dramatic conversion that St. Chad aided was that of the king’s two sons. Many years before, King Wulfhere had been baptized, but he had apostatized and returned to the pagan ways of his ancestors. His Christian wife had tried to raise their children as Christians, but the sons were kept from embracing the faith by their father. The brothers met Bishop Chad and, through many conversations, came to accept Christianity. King Wulfhere was so furious that he murdered his own sons in rage. Immediately, the king’s wife and daughter fled from him and entered a convent. In his loneliness, the king began to repent of his sins and eventually went to the bishop for forgiveness, asking to return to the Church.

Bishop Chad had a heavenly vision seven days before his death and he spent those days in prayer and giving last instructions to his monks. He reposed in the Lord on March 2 in the year 672, having lived a humble and faithful life devoted to the service of our Lord. Chad was immediately declared a saint by his people and many miracles of healing were reported near his relics.

May we remember this story of humility in the face of disputed and conflicting elections as we embark on our national elections, and may the prayers and witness of St. Chad help us as we strive for holiness in our own lives.